What Types of Trees Are in a Rainforest How Much Is a Baby Sloth

| Sloths[1] Temporal range: Early Oligocene to Holocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bradypus variegatus, a 3-toed sloth | |

| |

| Choloepus hoffmanni, a two-toed sloth | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Superorder: | Xenarthra |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Suborder: | Folivora Delsuc, Catzeflis, Stanhope, and Douzery, 2001[2] |

| Families | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Sloths are a group of arboreal Neotropical xenarthran mammals, constituting the suborder Folivora. Noted for their slowness of movement, they spend most of their lives hanging upside down in the trees of the tropical rainforests of South America and Central America. They are considered to exist most closely related to anteaters, together making up the xenarthran gild Pilosa.

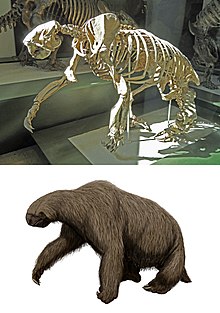

In that location are half dozen extant sloth species in two genera – Bradypus (iii–toed sloths) and Choloepus (two–toed sloths). Despite this traditional naming, all sloths actually have 3 toes on each rear limb, although two-toed sloths have simply two digits on each forelimb.[3] The 2 groups of sloths are from different, distantly related families, and are thought to have evolved their morphology via parallel evolution from terrestrial ancestors. As well the extant species, many species of ground sloths ranging up to the size of elephants (like Megatherium) inhabited both North and South America during the Pleistocene Epoch. However, they became extinct during the Quaternary extinction result around 12,000 years ago, together with nigh big bodied animals in the New Globe. The extinction correlates in time with the arrival of humans, but climate change has as well been suggested to have contributed. Members of an endemic radiation of Caribbean sloths formerly lived in the Greater Antilles. They included both footing and arboreal forms which became extinct afterward humans settled the archipelago in the mid-Holocene, effectually 6,000 years ago.

Sloths are so named because of their very low metabolism and deliberate movements. Sloth, related to slow, literally means "laziness," and their common names in several other languages (east.k. French paresseux) also hateful "lazy" or similar. Their slowness permits their low-free energy nutrition of leaves and avoids detection by predatory hawks and cats that hunt past sight.[iii] Sloths are almost helpless on the footing, only are able to swim.[4] The shaggy coat has grooved hair that is host to symbiotic greenish algae which camouflage the animal in the trees and provide information technology nutrients. The algae also attend sloth moths, some species of which exist solely on sloths.[v]

Taxonomy and evolution

Sloths vest to the superorder Xenarthra, a grouping of placental mammals believed to have evolved in the continent of S America around 60 million years ago.[six] One written report found that xenarthrans bankrupt off from other placental mammals around 100 million years ago.[7] Anteaters and armadillos are likewise included among Xenarthra. The primeval xenarthrans were arboreal herbivores with sturdy vertebral columns, fused pelvises, stubby teeth, and small-scale brains. Sloths are in the taxonomic suborder Folivora[ii] of the society Pilosa. These names are from the Latin 'leaf eater' and 'hairy', respectively. Pilosa is i of the smallest of the orders of the mammal class; its only other suborder contains the anteaters.

The Folivora are divided into at to the lowest degree 8 families, only two of which have living species; the residual are entirely extinct (†):[8]

- †Megalocnidae: the Greater Antilles sloths, a basal group that arose about 32 million years ago and became extinct most five,000 years ago.[viii]

- Superfamily Megatherioidea

- Bradypodidae, the three-toed sloths, contains iv extant species:

- The brown-throated 3-toed sloth is the near common of the extant species of sloth, which inhabits the Neotropical realm[1] [nine] in the forests of Due south and Central America.

- The pale-throated 3-toed sloth, which inhabits tropical rainforests in northern South America. It is similar in appearance to, and often confused with, the brown-throated three-toed sloth, which has a much wider distribution. Genetic evidence indicates the 2 species diverged effectually 6 million years agone.[10]

- The maned three-toed sloth, now found only in the Atlantic Woods of southeastern Brazil.

- The critically endangered pygmy 3-toed sloth which is endemic to the small island of Isla Escudo de Veraguas off the coast of Panama.

- †Megalonychidae: ground sloths that existed for about 35 meg years and went extinct about 11,000 years agone. This group was formerly idea to include both the ii-toed sloths and the extinct Greater Antilles sloths.

- †Megatheriidae: ground sloths that existed for about 23 million years and went extinct about 11,000 years agone; this family included the largest sloths.

- †Nothrotheriidae: ground sloths that lived from approximately 11.half-dozen million to 11,000 years ago. As well as basis sloths, this family included Thalassocnus, a genus of either semiaquatic or fully aquatic sloths.

- Bradypodidae, the three-toed sloths, contains iv extant species:

- Superfamily Mylodontoidea

- Choloepodidae, the two-toed sloths, contains two extant species:

- Linnaeus's two-toed sloth found in Venezuela, the Guianas, Colombia, Republic of ecuador, Peru, and Brazil north of the Amazon River.

- Hoffmann'southward two-toed sloth which inhabits tropical forests. Information technology has 2 separate ranges, dissever by the Andes. 1 population is plant from eastern Honduras[eleven] in the northward to western Ecuador in the southward, and the other in eastern Republic of peru, western Brazil, and northern Bolivia.[12]

- †Mylodontidae: ground sloths that existed for about 23 million years and went extinct about xi,000 years agone.

- †Scelidotheriidae: collagen sequence information indicates this grouping is more distant from Mylodon than Choloepus is, and so information technology has been elevated back to full family condition.[viii]

- Choloepodidae, the two-toed sloths, contains two extant species:

Evolution

The mutual ancestor of the two existing sloth genera dates to nearly 28 million years ago,[8] with similarities between the two- and three- toed sloths an example of convergent evolution to an arboreal lifestyle, "one of the near hit examples of convergent evolution known among mammals".[13] The ancient Xenarthra included a much greater diverseness of species, with a wider distribution, than those of today. Aboriginal sloths were by and large terrestrial, and some reached sizes that rival those of elephants, as was the case for Megatherium.[four]

Sloths arose in South America during its long period of isolation and somewhen spread to a number of the Caribbean islands likewise as North America. It is thought that swimming led to oceanic dispersal of pilosans to the Greater Antilles past the Oligocene, and that the megalonychid Pliometanastes and the mylodontid Thinobadistes were able to colonise North America about 9 million years agone, well before the formation of the Isthmus of Panama. The latter development, about three 1000000 years ago, allowed megatheriids and nothrotheriids to besides invade North America as part of the Bang-up American Interchange. Additionally, the nothrotheriid Thalassocnus of the west coast of South America became adapted to a semiaquatic and, somewhen, perhaps fully aquatic marine lifestyle.[14] In Republic of peru and Republic of chile, Thalassocnus entered the coastal habitat beginning in the tardily Miocene. Initially they just stood in the water, but over a span of 4 million years they somewhen evolved into swimming creatures, becoming specialist lesser feeders of seagrasses, similar to extant marine sirenians.[15]

Both types of extant tree sloth tend to occupy the aforementioned forests; in most areas, a item species of the somewhat smaller and generally slower-moving three-toed sloth (Bradypus) and a single species of the 2-toed type will jointly predominate. Based on morphological comparisons, it was thought the two-toed sloths nested phylogenetically inside 1 of the divisions of the extinct Greater Antilles sloths.[xvi] Though data has been collected on over 33 different species of sloths past analyzing os structures, many of the relationships between clades on a phylogenetic tree were unclear.[17] Much of the morphological bear witness collected to support the hypothesis of diphyly has been based on the structure of the inner ear.[18]

Recently obtained molecular data from collagen[8] and mitochondrial DNA sequences[19] autumn in line with the diphyly (convergent development) hypothesis, but have overturned some of the other conclusions obtained from morphology. These investigations consistently place two-toed sloths shut to mylodontids and three-toed sloths within Megatherioidea, close to Megalonyx, megatheriids and nothrotheriids. They brand the previously recognized family Megalonychidae polyphyletic, with both two-toed sloths and Greater Antilles sloths being moved away from Megalonyx. Greater Antilles sloths are now placed in a split, basal branch of the sloth evolutionary tree.[8] [19]

Phylogeny

The following sloth family phylogenetic tree is based on collagen and mitochondrial Dna sequence data (see Fig. 4 of Presslee et al., 2019).[eight]

| Folivora |

| |||||||||||||||||

Extinctions

The marine sloths of South America'due south Pacific declension became extinct at the end of the Pliocene following the closing of the Central American Seaway; this acquired a cooling trend in the littoral waters which killed off much of the area's seagrass (and which would take also made thermoregulation hard for the sloths, with their tiresome metabolism).[20]

Ground sloths disappeared from both North and South America before long later on the advent of humans about 11,000 years ago. Testify suggests human hunting contributed to the extinction of the American megafauna. Ground sloth remains found in both Northward and Due south America indicate that they were killed, cooked, and eaten past humans.[4] Climatic change that came with the terminate of the last ice historic period may have also played a role (although previous similar glacial retreats were not associated with similar extinction rates).

Megalocnus and some other Caribbean sloths survived until about five,000 years ago, long after ground sloths had died out on the mainland, but and so went extinct when humans finally colonized the Greater Antilles.[21]

Biology

Morphology and anatomy

Sloths can exist 60 to 80 cm (24 to 31 in) long and, depending on the species, weigh from 3.6 to 7.7 kg (7.9 to 17.0 lb). Two-toed sloths are slightly larger.[22] Sloths have long limbs and rounded heads with tiny ears. Three-toed sloths also accept stubby tails about 5 to 6 cm (ii.0 to ii.iv in) long.

Sloths are unusual amid mammals in non having seven cervical vertebrae. 2-toed sloths have five to seven, while three-toed sloths have viii or nine. The other mammals not having seven are the manatees, with six.[23]

Physiology

Sloths take colour vision, just have poor visual acuity. They also have poor hearing. Thus, they rely on their sense of olfactory property and touch to find food.[24]

Sloths take very low metabolic rates (less than half of that expected for a mammal of their size), and depression body temperatures: 30 to 34 °C (86 to 93 °F) when active, and nonetheless lower when resting. Sloths are heterothermic, significant their body temperature may vary according to the environment, normally ranging from 25 to 35 °C (77 to 95 °F), just able to drop to equally low every bit 20 °C (68 °F), inducing torpor.[24]

The outer hairs of sloth fur abound in a direction opposite from that of other mammals. In well-nigh mammals, hairs abound toward the extremities, but because sloths spend so much time with their limbs to a higher place their bodies, their hairs abound away from the extremities to provide protection from the elements while they hang upside down. In most conditions, the fur hosts symbiotic algae, which provide camouflage[25] from predatory jaguars, ocelots,[26] and harpy eagles.[27] Because of the algae, sloth fur is a pocket-size ecosystem of its own, hosting many species of commensal and parasitic arthropods.[28] At that place are a big number of arthropods associated with sloths. These include biting and blood-sucking flies such equally mosquitoes and sandflies, triatomine bugs, lice, ticks and mites. Sloths accept a highly specific community of commensal beetles, mites and moths.[29] The species of sloths recorded to host arthropods include[29] the pale-throated three-toed sloth, the brown-throated 3-toed sloth, and Linnaeus'southward ii-toed sloth. Sloths benefit from their relationship with moths because the moths are responsible for fertilizing algae on the sloth, which provides them with nutrients.[30]

Action

Their limbs are adapted for hanging and grasping, not for supporting their weight. Muscles make upwards only 25 to thirty per centum of their total trunk weight. Most other mammals have a musculus mass that makes up 40 to 45 pct of their full trunk weight.[31] Their specialised hands and feet take long, curved claws to let them to hang upside downwards from branches without attempt,[32] and are used to drag themselves along the ground, since they cannot walk. On iii-toed sloths, the artillery are 50 per centum longer than the legs.[24]

Sloths move only when necessary and even then very slowly. They usually movement at an average speed of iv metres (13 ft) per minute, only tin can move at a marginally higher speed of 4.v metres (15 ft) per minute if they are in firsthand danger from a predator. While they sometimes sit on top of branches, they usually eat, sleep, and fifty-fifty requite nascence hanging from branches. They sometimes remain hanging from branches even after death. On the ground, the maximum speed of sloths is 3 metres (9.8 ft) per infinitesimal. Two-toed sloths are generally meliorate able than three-toed sloths to disperse between clumps of trees on the footing.[33]

Sloths are surprisingly strong swimmers and tin can reach speeds of 13.five metres (44 ft) per minute.[34] They utilise their long artillery to paddle through the h2o and can cantankerous rivers and swim between islands.[35] Sloths can reduce their already tedious metabolism even further and slow their heart charge per unit to less than a third of normal, allowing them to hold their breath underwater for upwards to 40 minutes.[36]

Wild brownish-throated three-toed sloths sleep on average 9.vi hours a 24-hour interval.[37] Two-toed sloths are nocturnal.[38] 3-toed sloths are mostly nocturnal, but can be active in the twenty-four hours. They spend 90 per cent of their time motionless.[24]

Behavior

Sloths are solitary animals that rarely interact with one some other except during breeding season,[39] though female sloths do sometimes congregate, more than and so than do males.[40]

Diet

Babe sloths learn what to eat by licking the lips of their mother.[41] All sloths eat the leaves of the cecropia.

Two-toed sloths are omnivorous, with a various diet of insects, carrion, fruits, leaves and small lizards, ranging over up to 140 hectares (350 acres). Three-toed sloths, on the other mitt, are almost entirely herbivorous (plant eaters), with a limited nutrition of leaves from merely a few copse,[39] and no other mammal digests its food every bit slowly.

They accept made adaptations to arboreal browsing. Leaves, their master nutrient source, provide very footling energy or nutrients, and do not digest hands, and so sloths have large, irksome-interim, multi-chambered stomachs in which symbiotic bacteria pause down the tough leaves.[39] Every bit much as 2-thirds of a well-fed sloth's body weight consists of the contents of its breadbasket, and the digestive process can accept a month or more to complete.

Iii-toed sloths become to the footing to urinate and defecate about once a week, digging a hole and covering it later on. They get to the same spot each time and are vulnerable to predation while doing and so. Considering the large energy expenditure and dangers involved in the journey to the ground, this behaviour has been described equally a mystery.[42] [43] [44] Recent research shows that moths, which live in the sloth'southward fur, lay eggs in the sloth'due south feces. When they hatch, the larvae feed on the feces, and when mature wing up onto the sloth above. These moths may take a symbiotic relationship with sloths, every bit they live in the fur and promote growth of algae, which the sloths consume.[5] Individual sloths tend to spend the bulk of their time feeding on a unmarried "modal" tree; by burying their excreta near the trunk of that tree, they may too help attend it.

Reproduction

The pale- and brown-throated iii-toed sloths mate seasonally, while the maned three-toed sloth breeds at whatsoever time of the year. The reproduction of pygmy iii-toed sloths is unknown. Litters are of one newborn just, after vi months' gestation for 3-toed, and 12 months' for 2-toed. Newborns stay with their female parent for about five months. In some cases, young sloths die from a fall indirectly because the mothers prove unwilling to go out the safety of the trees to think the young.[46] Females usually deport one infant every year, but sometimes sloths' low level of motility actually keeps females from finding males for longer than 1 year.[47] Sloths are not especially sexually dimorphic and several zoos have received sloths of the incorrect sex.[48] [49]

The boilerplate lifespan of ii-toed sloths in the wild is currently unknown due to a lack of full-lifespan studies in a natural environs.[l] Median life expectancy in human care is about 16 years, with i private at the Smithsonian Institution'south National Zoo reaching an age of 49 years before her expiry.[51]

Distribution

Although habitat is limited to the tropical rainforests of Cardinal and South America, in that environment sloths are successful. On Barro Colorado Island in Panama, sloths have been estimated to contain 70% of the biomass of arboreal mammals.[52] Iv of the half dozen living species are presently rated "least business"; the maned three-toed sloth (Bradypus torquatus), which inhabits Brazil's dwindling Atlantic Woods, is classified as "vulnerable",[53] while the island-dwelling pygmy three-toed sloth (B. pygmaeus) is critically endangered. Sloths' lower metabolism confines them to the tropics and they adopt thermoregulation behaviors of cold-blooded animals such as sunning themselves.[54]

Human relations

The majority of recorded sloth deaths in Costa Rica are due to contact with electrical lines and poachers. Their claws also provide another, unexpected deterrent to human being hunters; when hanging upside-downward in a tree, they are held in identify past the claws themselves and often practise not fall down even if shot from below.

Sloths are victims of animal trafficking where they are sold as pets. However, they brand very poor pets, as they have such a specialized ecology.[55]

The founder and director of the Green Heritage Fund Suriname, Monique Puddle, has helped rescue and release more than 600 sloths, anteaters, armadillos, and porcupines.[56]

The Sloth Institute Costa rica is known for caring, rehabilitating and releasing sloths dorsum into the wild.[57] Also in Costa rica, the Aviarios Sloth Sanctuary cares for sloths. It has rehabilitated and released about 130 individuals back into the wild.[58] However, a report in May 2016 featured two former veterinarians from the facility who were intensely critical of the sanctuary'south efforts, accusing it of mistreating the animals.[59]

References

- ^ a b Gardner, A. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the Earth: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (third ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 100–101. ISBN978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Delsuc, Frédéric; Catzeflis, François Thou.; Stanhope, Michael J.; Douzery, Emmanuel J. P. (vii August 2001). "The development of armadillos, anteaters and sloths depicted by nuclear and mitochondrial phylogenies: implications for the status of the enigmatic fossil Eurotamandua". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 268 (1476): 1605–1615. doi:ten.1098/rspb.2001.1702. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC1088784. PMID 11487408.

- ^ a b "Overview". The Sloth Conservation Foundation. Retrieved 29 Nov 2017.

- ^ a b c The Land and Wildlife of South America . Time Inc. 1964. pp. 15, 54.

- ^ a b Bennington-Castro, Joseph. "The Strange Symbiosis Between Sloths and Moths". Gizmodo . Retrieved 1 Dec 2017.

- ^ O'Leary, Maureen A.; Bloch, Jonathan I.; Flynn, John J.; Gaudin, Timothy J.; Giallombardo, Andres; Giannini, Norberto P.; Goldberg, Suzann L.; Kraatz, Brian P.; Luo, Zhe-11 (8 Feb 2013). "The Placental Mammal Antecedent and the Mail service–Yard-Pg Radiation of Placentals". Scientific discipline. 339 (6120): 662–667. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..662O. doi:ten.1126/science.1229237. hdl:11336/7302. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 23393258. S2CID 206544776.

- ^ Svartman, Marta; Rock, Gary; Stanyon, Roscoe (21 July 2006). "The Ancestral Eutherian Karyotype Is Nowadays in Xenarthra". PLOS Genetics. ii (7): e109. doi:10.1371/periodical.pgen.0020109. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC1513266. PMID 16848642.

- ^ a b c d e f thou Presslee, S.; Slater, G. J.; Pujos, F.; Forasiepi, A. G.; Fischer, R.; Molloy, K.; Mackie, M.; Olsen, J. 5.; Kramarz, A.; Taglioretti, One thousand.; Scaglia, F.; Lezcano, Thousand.; Lanata, J. 50.; Southon, J.; Feranec, R.; Bloch, J.; Hajduk, A.; Martin, F. M.; Gismondi, R. S.; Reguero, Thou.; de Muizon, C.; Greenwood, A.; Chait, B. T.; Penkman, K.; Collins, M.; MacPhee, R.D.E. (2019). "Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships" (PDF). Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (7): 1121–1130. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z. PMID 31171860. S2CID 174813630.

- ^ Gardner, Alfred L. (2007). "Suborder Folivora". In Gardner, Alfred L. (ed.). Mammals of Southward America, Volume i: Marsupials, Xenarthrans, Shrews, and Bats. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 157–168 (p. 161). ISBN978-0-226-28240-4.

- ^ Moraes-Barros, Grand.C.; et al. (2011). "Morphology, molecular phylogeny, and taxonomic inconsistencies in the written report of Bradypus sloths (Pilosa: Bradypodidae)". Journal of Mammalogy. 92 (1): 86–100. doi:x.1644/10-MAMM-A-086.1.

- ^ Plese, T.; Chiarello, A. (2014). "Choloepus hoffmanni". IUCN Cherry-red List of Threatened Species. 2014: east.T4778A47439751. doi:x.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T4778A47439751.en.

- ^ Hayssen, V. (2011). "Choloepus hoffmanni (Pilosa: Megalonychidae)". Mammalian Species. 43 (1): 37–55. doi:x.1644/873.one.

- ^ Gaudin, T.J. (1 February 2004). "Phylogenetic relationships among sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Tardigrada): the craniodental evidence". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 140 (2): 255–305. doi:x.1111/j.1096-3642.2003.00100.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Muizon, C. de; McDonald, H. G.; Salas, R.; Urbina, Chiliad. (June 2004). "The evolution of feeding adaptations of the aquatic sloth Thalassocnus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (2): 398–410. doi:x.1671/2429b. JSTOR 4524727. S2CID 83859607.

- ^ Amson, E.; Muizon, C. de; Laurin, 1000.; Argot, C.; Buffrénil, Five. de (2014). "Gradual adaptation of bone construction to aquatic lifestyle in extinct sloths from Republic of peru". Proceedings of the Royal Social club B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1782): 20140192. doi:x.1098/rspb.2014.0192. PMC3973278. PMID 24621950.

- ^ White, J.L.; MacPhee, R.D.E. (2001). "The sloths of the Due west Indies: a systematic and phylogenetic review". In Forest, C.A.; Sergile, F.E. (eds.). Biogeography of the W Indies: Patterns and Perspectives. Boca Raton, London, New York, and Washington, D.C.: CRC Press. pp. 201–235. doi:10.1201/9781420039481-14. ISBN978-0-8493-2001-9.

- ^ Gaudin, Timothy (2004). "Phylogenetic Relationships among Sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Tardigrada): The Craniodental Evidence". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 140 (2): 255–305. doi:ten.1111/j.1096-3642.2003.00100.x.

- ^ Raj Pant, Sara; Goswami, Anjali; Finarelli, John A (2014). "Circuitous body size trends in the evolution of sloths (Xenarthra: Pilosa)". BMC Evolutionary Biological science. fourteen: 184. doi:x.1186/s12862-014-0184-1. PMC4243956. PMID 25319928.

- ^ a b Delsuc, F.; Kuch, M.; Gibb, G. C.; Karpinski, E.; Hackenberger, D.; Szpak, P.; Martínez, J. G.; Mead, J. I.; McDonald, H. Chiliad.; MacPhee, R.D.Eastward.; Barracks, Thousand.; Hautier, 50.; Poinar, H. N. (2019). "Ancient Mitogenomes Reveal the Evolutionary History and Biogeography of Sloths". Current Biology. 29 (12): 2031–2042.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043. PMID 31178321.

- ^ Amson, Due east.; Argot, C.; McDonald, H. G.; de Muizon, C. (2015). "Osteology and functional morphology of the centric postcranium of the marine sloth Thalassocnus (Mammalia, Tardigrada) with paleobiological implications". Journal of Mammalian Development. 22 (4): 473–518. doi:ten.1007/s10914-014-9280-vii. S2CID 16700349.

- ^ Steadman, D. W.; Martin, P. Southward.; MacPhee, R. D. Eastward.; Jull, A. J. T.; McDonald, H. Grand.; Forest, C. A.; Iturralde-Vinent, G.; Hodgins, G. Westward. Fifty. (16 August 2005). "Asynchronous extinction of tardily Quaternary sloths on continents and islands". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102 (33): 11763–11768. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10211763S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502777102. PMC1187974. PMID 16085711.

- ^ "Sloth". National Geographic. March 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ "Sticking their necks out for development: Why sloths and manatees have unusually long (or short) necks". ScienceDaily . Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Sloth". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 1 Dec 2017.

- ^ Suutari, Milla; Majaneva, Markus; Fewer, David P.; Voirin, Bryson; Aiello, Annette; Friedl, Thomas; Chiarello, Adriano G.; Blomster, Jaanika (1 January 2010). "Molecular evidence for a various dark-green algal community growing in the hair of sloths and a specific clan with Trichophilus welckeri(Chlorophyta, Ulvophyceae)". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10: 86. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-x-86. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC2858742. PMID 20353556.

- ^ Moreno, Ricardo S.; Kays, Roland W.; Samudio, Rafael (24 August 2006). "Competitive Release in Diets of Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) and Puma (Puma concolor) afterward Jaguar (Panthera onca) Decline". Journal of Mammalogy. 87 (4): 808–816. doi:10.1644/05-MAMM-A-360R2.i. ISSN 0022-2372.

- ^ Aguiar-Silva, F. Helena; Sanaiotti, Tânia Yard.; Luz, Benjamim B. (1 March 2014). "Food Habits of the Harpy Eagle, a Top Predator from the Amazonian Rainforest Canopy". Journal of Raptor Enquiry. 48 (1): 24–35. doi:10.3356/JRR-13-00017.one. ISSN 0892-1016. S2CID 86270583.

- ^ Gilmore, D. P.; Da Costa, C. P.; Duarte, D. P. F. (1 Jan 2001). "Sloth biology: an update on their physiological environmental, beliefs and role as vectors of arthropods and arboviruses". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 34 (1): 9–25. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2001000100002. ISSN 0100-879X. PMID 11151024.

- ^ a b Gilmore, D. P.; Da Costa, C. P.; Duarte, D. P. F. (2001). "Sloth biology: an update on their physiological ecology, behavior and part as vectors of arthropods and arboviruses" (PDF). Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 34 (1): 9–25. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2001000100002. ISSN 1678-4510. PMID 11151024.

- ^ Ed Yong (21 Jan 2014). "Can Moths Explain Why Sloths Poo on the Ground?". Phenomena.

- ^ "What Does It Mean to Be a Sloth?". natureinstitute.org . Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ Mendel, Frank C. (1 Jan 1985). "Use of Hands and Feet of 3-Toed Sloths (Bradypus variegatus) during Climbing and Terrestrial Locomotion". Journal of Mammalogy. 66 (2): 359–366. doi:x.2307/1381249. JSTOR 1381249.

- ^ Garcés‐Restrepo, Thousand.F.; Pauli, J.N.; Peery, One thousand.Z. (2018). "Natal dispersal of tree sloths in a human-dominated landscape: Implications for tropical biodiversity conservation". Periodical of Applied Ecology. 55 (5): 2253–2262. doi:ten.1111/1365-2664.13138.

- ^ Goffart, Chiliad. (1971). "Function and Form in the sloth". International Series of Monographs in Pure and Practical Biology. 34: 94–95.

- ^ BBC (4 Nov 2016), Swimming sloth - Planet Earth II: Islands Preview - BBC One, archived from the original on 30 October 2021, retrieved 17 April 2017

- ^ Britton, S. Westward. (1 January 1941). "Form and Function in the Sloth". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 16 (1): thirteen–34. doi:10.1086/394620. JSTOR 2808832. S2CID 85162387.

- ^ Briggs, Helen (13 May 2008). "Article "Sloth'due south Lazy Image 'A Myth'"". BBC News. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ^ Eisenberg, John F.; Redford, Kent H. (fifteen May 2000). Mammals of the Neotropics, Volume 3: The Cardinal Neotropics: Republic of ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil. University of Chicago Press. pp. 624 (see pp. 94–95, 97). ISBN978-0-226-19542-i. OCLC 493329394.

- ^ a b c Alina Bradford (26 November 2018). "Sloths: The World's Slowest Mammals". Live Scientific discipline.

- ^ "Sloth". Animate being Corner.

- ^ Venema, Vibeke (4 April 2014). "The adult female who got 'slothified'". BBC News . Retrieved 1 Dec 2017.

- ^ "The 'Decorated' Life of the Sloth | BBC Globe". YouTube. 18 May 2009. Retrieved xi Feb 2022.

- ^ "The greatest mystery of sloth pooping has been solved". 23 January 2014.

- ^ "Welcome to the US Petabox". Archived from [Title:A syndrome of mutualism reinforces the lifestyle of a sloth Authors:Jonathan Due north. Pauli, Jorge E. Mendoza, Shawn A. Steffan, Cayelan C.Carey, Paul J. Weimer and K. Zachariah Peery Journal:Proceedings of the Majestic Society B the original] on 15 July 2013.

- ^ Soares, C. A.; Carneiro, R. Southward. (1 May 2002). "Social behavior between mothers × young of sloths Bradypus variegatus SCHINZ, 1825 (Xenarthra: Bradypodidae)". Brazilian Journal of Biological science. 62 (2): 249–252. doi:10.1590/S1519-69842002000200008. ISSN 1519-6984. PMID 12489397.

- ^ Pauli, Jonathan Due north.; Peery, M. Zachariah (19 December 2012). "Unexpected Stiff Polygyny in the Brown-Throated Three-Toed Sloth". PLOS I. 7 (12): e51389. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...751389P. doi:ten.1371/journal.pone.0051389. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC3526605. PMID 23284687.

- ^ "Manly secret of not-mating sloth at London Zoo". BBC News. BBC. 19 August 2010. Retrieved 30 Apr 2015.

- ^ "Same-sex sloths dash Drusillas convenance programme". BBC News. BBC. 5 December 2013. Retrieved thirty April 2015.

- ^ "About the Sloth". Sloth Conservation Foundation . Retrieved 31 Oct 2019.

- ^ "Southern 2-toed sloth". Smithsonian'south National Zoo. 25 April 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Eisenberg, John F.; Redford, Kent H. (xv May 2000). Mammals of the Neotropics, Volume 3: The Central Neotropics: Ecuador, Republic of peru, Bolivia, Brazil. University of Chicago Press. pp. 624 (see p. 96). ISBN978-0-226-19542-i. OCLC 493329394.

- ^ Chiarello, A. & Moraes-Barros, Due north. (2014). "Bradypus torquatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T3036A47436575. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T3036A47436575.en.

- ^ Dowling, Stephen (29 Baronial 2019). "Why do sloths motility and so slowly?". BBC Futurity. BBC News. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ "Sloths: Hottest-Selling Animal in Republic of colombia'due south Illegal Pet Trade". ABC News. 29 May 2013. Retrieved 2 Dec 2017.

- ^ "When sloths are in trouble, she'southward the one to telephone call". CNN . Retrieved one December 2017.

- ^ "The Sloth Institute website".

- ^ Sevcenko, Melanie (17 April 2013). "Sloth sanctuary nurtures animals dorsum to health". Deutsche Welle . Retrieved xviii April 2013.

- ^ Schelling, Ameena (19 May 2016). "Famous Sloth Sanctuary Is A Nightmare For Animals, Ex-Workers Say". The Dodo . Retrieved twenty May 2016.

External links

bardolphyetlenownew.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sloth

0 Response to "What Types of Trees Are in a Rainforest How Much Is a Baby Sloth"

Post a Comment